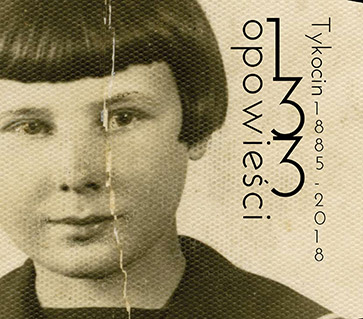

Exhibition "133 stories" as "Adie Memoirs"

Introduction by Alan Duben

An oil painting depicting a local windmill destroyed by the Russian army in 1918, a home-sewn Polish flag celebrating the newly emerging Second Republic dating from 1918, a Russian passport used by a Jewish girl from Tykocin for her emigration to America in 1906, a photo relating to the emigration of a Christian family to the U.S. in 1889, a postcard sent from Paris in 1922, an address book from the same year, the program of a Constitution Day celebration with Jews and Christians arm in arm, photographs of two Christian school girls separated by war who never again met, a very old broken rafter’s pipe found at the bottom of the Narew, photographs of Jewish traders of timber from the interwar period, an old radio, a photograph of the fire brigade from 1937, a photo of the old Hetman cinema, audio recordings relating to the mass murder of the Jews of Tykocin in 1941, a notarial document for the sale of a windmill, an official register from the Liquidation Committee from the 1940s listing “abandoned” (Jewish) properties with the names of the new owners recorded in place of the former owners who were indicated merely as “Jewish owner gone”, a document used for the purchase of a Jewish home in 1946, family letters, documents relating to the status of the town in the 1950s, cobblers’ tools, an old Seder plate, a photograph of the desk clock of the Jewish town doctor, documents relating to the reconstruction of the town in the 1950s, photographs of the town in the 1960s and 70s, the beginnings of tourism in Tykocin: photos of Polish students visiting Tykocin as a tourists in the 1970s, a 100 year old child’s shoe discovered in the attic of a house undergoing renovation, an old hammer, and an ordinary milk jug. These are just some of the quotidian objects and images or what might be called “aide memoires” to be found now on exhibit at 10 Czarnieckiego Square. Perhaps one of the most telling objects is a Catholic prayer book with bookmarks cut from family letters, from a 1944 German passport, and from a fragment of a Jewish newspaper. What do all these things tell us about life in Tykocin in the past, both individually, as a group and perhaps even in sum? What do they share in common?

Tykocin is a small town with a distinguished and a tragic history. Its towering eighteenth century cathedral standing at one end of the town center and its grand seventeenth century synagogue at the other are monuments to its two major communities, the Catholics and the Jews that shared and were dominant in the town over hundreds of years up until 1941. Much is known about Tykocin: as a royal town, home to members of the court, and the depository of the royal treasury, the library, archives, and the arsenal of King Zygmunt August. For centuries it was the center of the Jewish community of the whole Podlasie region. On the Catholic side, we know the story of Tykocin’s nobles, its priests, and of retired military officers who resided at Alumnat. For the Jews, rabbis, Talmudic scholars, and merchants stand out, and the names of some are known.

This town, far from the centers of state or imperial power, has been the scene of relentless invasions over the centuries, from the West by the armies of Prussia, then Imperial Germany, and from the East by Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union. In the past, world history played itself out on a grand scale, often with great brutality in this town that rarely exceeded 5,000 inhabitants. In 1941 almost all of the Jews, half the population of the town, were murdered by German invaders, and local history as it had been known over long centuries of living together came to an abrupt halt. One gets the feeling today that in the aftermath of the traumas of its past, Tykocin, now diminished in numbers and sidelined, is left celebrating its past, gazing back in a state of silent disquietude. Flocks of Polish and Jewish tourists come to experience the nostalgia of a quaint “old-time” Polish town or of an idealized Jewish shtetl, or both. Others come to remember the Jews murdered in 1941. Both the nostalgia of an idealized past, the horrors of the destruction of the Jewish community, and the suffering of Christian residents at the hands of the Germans and the Soviets are indelible parts of the heritage of Tykocin. Tykocin today derives some of its income, and its new-found fame, from tourism – an unsettling tourism built both on its past and present character and beauties, as well as from the devastation the town experienced during World War II.

While much is known about the history of Tykocin, there is little record of the lives of the majority of people who ever lived here. It is not possible to tell the story of Tykocin of the past without telling a tale of both Christians and Jews, as the lives of these two peoples were densely intertwined as neighbors and in the marketplace, while at the same time quite separate in many ways. Their lives were at the same time both very familiar and very alien to each other. The historical character of Tykocin was built on that complex relationship and the mutual dependency of farmers and traders and craftsmen, Christians and Jews, and the relationship of noblemen and priests and rabbis with all of them. “Do you know what makes every town Polish?” nineteenth century literary figure Ignacy Kraszewski once asked. “The Jews,” he replied. “When there are no more Jews, we enter an alien country….” Objects from the exhibition attest to that dense relationship.

During the past thirty years or so, a “new” history has emerged in many parts of the world, a history seeking to tell the story of the way ordinary people lived their lives. Some refer to this as a kind of “history from below” in contrast to the glorious histories of kings and queens, the church, wars, and conquests that we all know so well from school. There are few records of the mundane, everyday existence of the overwhelming majority. Most live and die without leaving much of a trace for future use by historians or others. Objects from the past survive in homes often by chance, their provenance and local meaning frequently lost. Some emerge from the earth, often in pieces, others from dusty basements and attics. Luck is an important factor in their survival and rediscovery. When they reemerge they are fair game for diverse interpretation.

On another level there are church and state records: of births, baptisms, marriages, and of deaths. Collated as seemingly dry statistics, such figures have the potential to bring to life patterns of everyday life unknown even to those living at the time of recording. There are various legal documents, community records, and for the Jews, the memorial book Sefer Tiktin written by survivors after the war. And last but certainly not least, there are the material objects that have been passed down the generations. Among these are the old homes themselves that have survived the ravages of war and time, odd tools, household furnishings and goods, personal possessions, photographs, letters, and the like. When possible, our understanding of the most recent past also can also rest on retrospective oral accounts. Here the limitations of a life span and of memory set the boundaries of understanding.

Might displaying the everyday things found in this exhibition serve as a starting point, perhaps one might even say an aide memoires, a “talking point”, in understanding the way people lived in Tykocin in the past? Do such objects or documents “speak for themselves,” are they repositories of local or domestic memory, or are they mute and dependent upon meanings we apply to them? If we don’t know the provenance of an object is its story lost, its meaning diminished? Who is to tell the story of quotidian objects: the most recent owners, former owners, or outsiders who are able to put diverse sources together in a way locals often cannot? Everyone’s home is a kind of museum in this sense, and all the objects found there carry various degrees of meaning, some even distinct memories, for its residents. Some carry memories known to the family, for others the memories may have been lost over the generations, for still others, objects found in homes today may carry painful or regretful connections with the past which are difficult to deal with. What other surprises, what other objects from the lives of the people of Tykocin might lie hidden in the attics of their homes, might have long gone unnoticed on dusty shelves, been locked away and forgotten in drawers or chests, or stored in closets and are yet to be brought to life again and shared? What will all of this mean?

Alan Duben June 2018